Roche raised hopes this year that it has a future blockbuster drug on its hands after early trial results of the Swiss drug group’s new obesity treatment showed rapid weight loss among recipients.

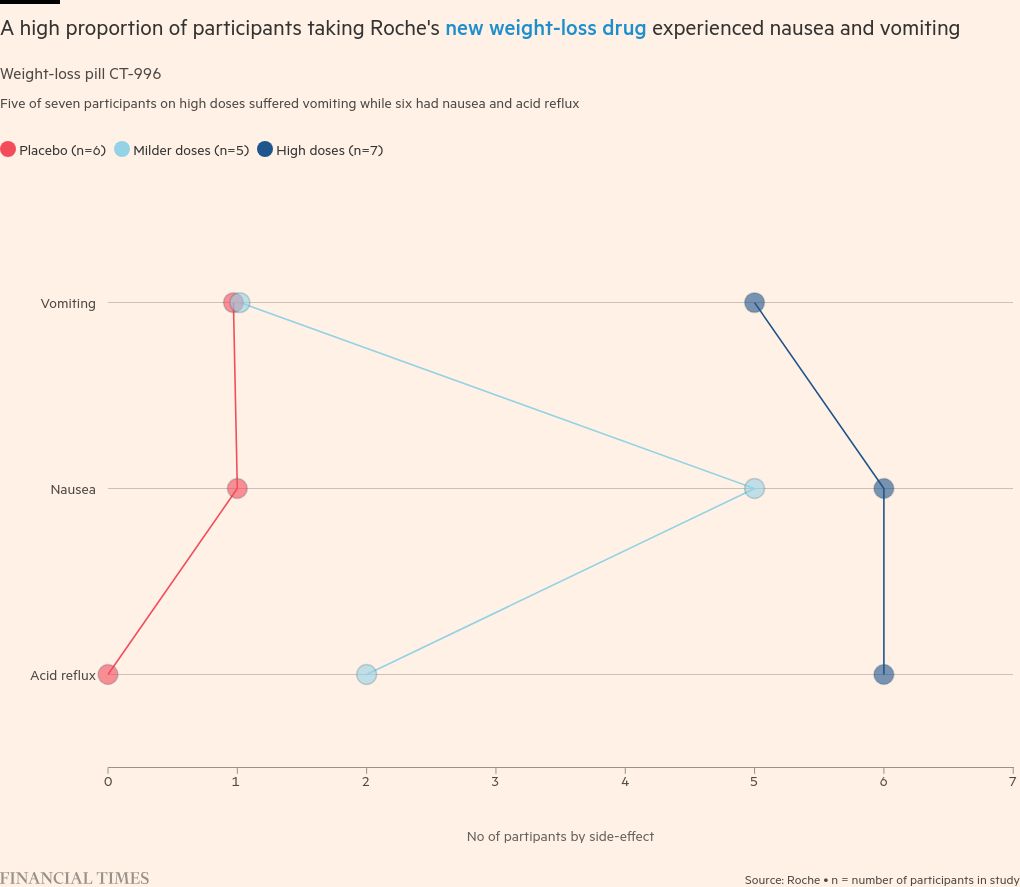

But revelations earlier this week of vomiting and other side effects among people who took strong doses of the drug unsettled investors and highlighted the challenges facing businesses looking to break into the lucrative new market for “GLP-1” drugs.

The company’s shares fell 4 percent on Monday after it was revealed that three-quarters of patients who took the highest dose of its CT-388 vaccine suffered from vomiting. They fell another 5 percent on Thursday after similar data for its oral weight loss pills.

The backlash is a reminder that not all patients can afford the new class of weight-loss therapies dominated by Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly — and that challengers to the industry’s pioneers face significant hurdles.

Treatment was a major talking point at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes conference in Madrid this week.

Peter Verdelt, a Citigroup analyst attending the conference, said Roche had created problems for itself by touting its preliminary trial results in July as “really special data”.

“I don’t think anyone can say that now,” he said. “They prepared for a fall.”

Global drugmakers Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly are vying to capture the lead in the lucrative and fast-growing GLP-1 drug market.

Nearly one in 10 of the 1,150 research abstracts presented at the Madrid conference included GLP-1 drugs.

The drug has proven an effective way to control weight and treat diabetes, and Goldman Sachs analysts estimate that the market for the product could grow to $130 billion annually by 2030.

The new drugs work by mimicking the GLP-1 hormone, which lowers blood sugar and curbs appetite. Treatments like Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro add another GIP hormone to promote weight loss. In addition, companies are experimenting with other gut and pancreatic hormones.

Francine Kaufman, former head of the American Diabetes Association and now chief medical officer of Senseonics, a medical device company, said the drugs revolutionized diabetes treatment at a time when obesity rates were rising.

“I said in the 2000s that we need a silver bullet,” she said. “It came.”

GLP-1-based drugs, however, are associated with vomiting, nausea, and constipation, especially at higher doses. They are also associated with muscle wasting in some experiments. The US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency have recently explored more serious side effects — such as suicidal thoughts — reported with the drug, but found no evidence of a link.

Defending the potential of Roche’s drug, Manu Chakravarthy, who leads the company’s metabolic product development, said it needed to “increase the tolerability” of its drug, and that side effects at high doses are consistent with other GLP-1-based drugs.

Chakraborty added that it is unlikely that users of Roche products will receive such a high dose or rapid increase in future trials.

“We are encouraged because it cannot get any worse than this,” he said.

Drug manufacturers use early trials to test the safety of their drugs and often test higher doses. Verdult said that when Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly presented data on their drugs years ago, they were also concerned about side effects.

At the Madrid conference, Novo Nordisk presented data on a new drug – oral amycretin – that caused vomiting in more than half of users of the highest dose.

Side effects seem to deter some patients. Research published this year by Blue Health Intelligence found that 30 percent of GLP-1 users stopped treatment within four weeks of starting, with side effects being a significant factor. Cost and availability of drugs is also a factor.

Former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson wrote in a column in the Daily Mail last year that the vomiting associated with taking the diabetes treatment Ozempic off-label was intolerable.

Other drugmakers have struggled to develop so-called small-molecule pills — synthetic drugs that are easier to produce at scale than weight-loss shots.

Pfizer abandoned a twice-daily version of its weight-loss drug danuglipron after reports of excessive nausea and vomiting in mid-stage trials. But the New York-based drugmaker is pushing ahead with a modified version of the daily.

To deal with side effects, companies develop alternative formulations of drugs. Analysts have noted excitement about the pancreatic hormone amylin, which may reduce drug-related muscle wasting, but this has yet to be proven at scale.

Novo Nordisk’s next product – CagriSema – combines GLP-1s with an amylin analogue. The drugmaker will report data from the product later this year.

Eli Lilly has made several deals to address the issue of muscle wasting. Last year it spent $1.9 billion to acquire Versanis, whose lead drug is based on the hormone Activin, which helps regulate muscle mass. It also partners with BioAge, a company that develops a muscle regeneration drug. BioAge recently filed for an initial public offering.

But the emerging data further underscore how much companies, investors and scientists still have to discover about how GLP-1 therapies work.

Among the studies presented in Madrid, Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro drug led to more effective weight loss in women than in men, but caused increased nausea and vomiting.

Luis-Emilio García-Perez, the Eli Lilly scientist who conducted the study, said the company doesn’t know why the results differed between the two groups.

Ilya Yuffa, Eli Lilly’s head of international operations, said it was still unclear whether the new treatment would have fewer side effects and allow the drug to become more widely available.

“For other molecules in development that may have new approaches, I think it’s probably too early to have a clear view of what they look like in a broader population,” Ufa said.

#Roche #data #show #stomachupsetting #side #effects #weightloss #drugs